A brief history of computing

In the beginning, there was the voice. The Aboriginal people used songlines, physical paths through the landscape linked with songs, encoding stories and knowledge across generations. Then, we discovered drawing, on stone: early humans used mineral pigments to draw animals, humans, and abstract signs on the walls of caves – inventing a persistent storage system for information that's endured for millenia...

Fast-forward ~20,000 years, and we have the International Business Machines Corporation, which sells the first mass-produced computer in 1953. The first unit was sold to the John Hancock Insurance Company. Back then, computers were only accessible to large corporations, because they were gigantic, obscenely expensive ($1.5 million in today's dollars!), and absurdly difficult to program.

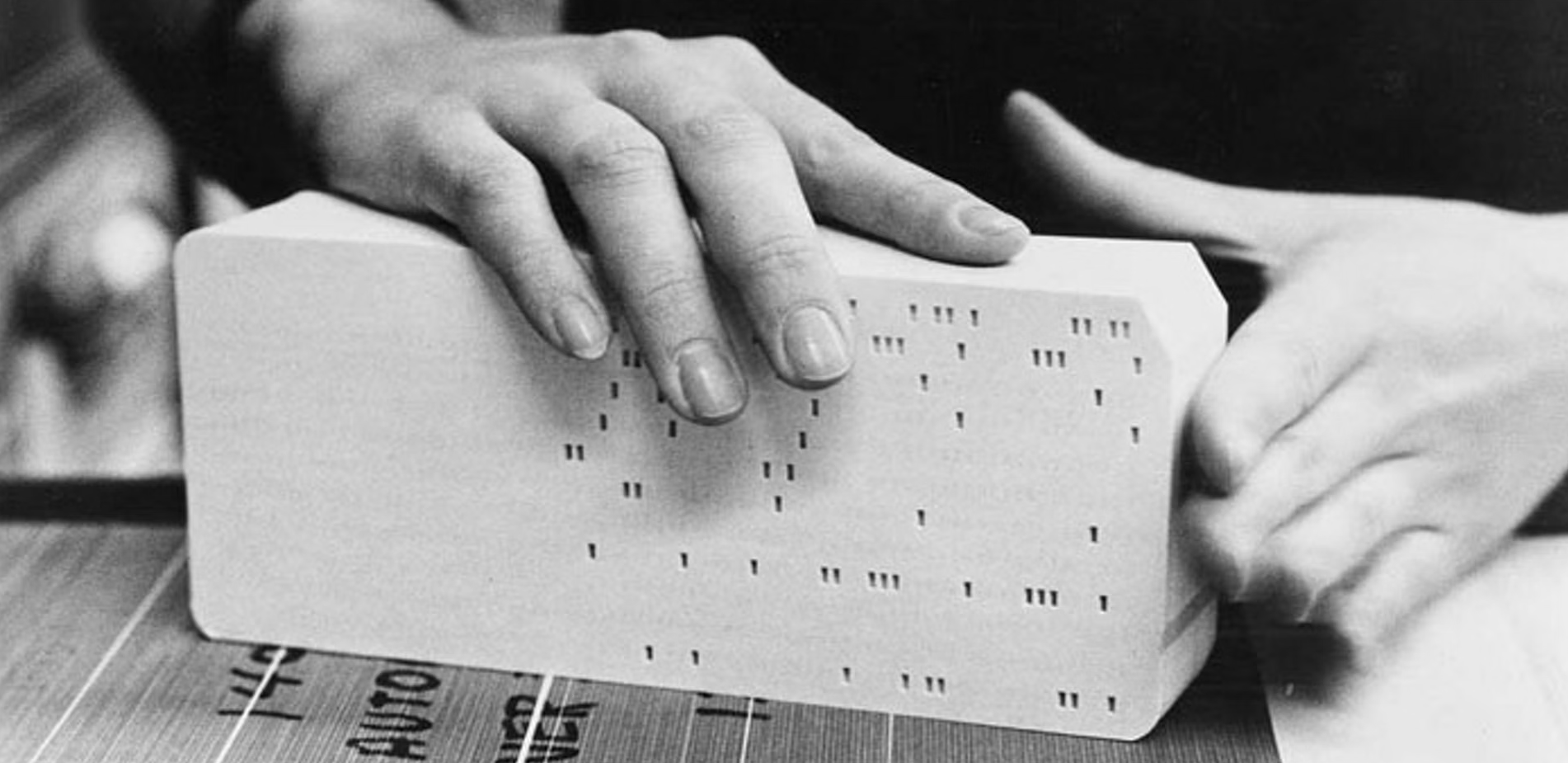

For a while, interacting with a computer generally looked like this: you punched holes in cards or paper tape, painstakingly crafting a "program" (a stack of cards or a long strip of tape) and praying that you didn't make any mistakes. It was painful, but it was the beginning of something remarkable. A system for transferring instructions from humans to primitive machine "minds".

In the 1960s and 1970s, punch cards gave way to programming languages like FORTRAN and COBOL (still arcane, but much more approachable than a grid of 1s and 0s), and the teleprinter (essentially a typewriter hooked up to a computer) which let you send commands from your desk and get responses back, printed on paper. The applications in the workplace were immense, and IBM’s System/360/370 era made the company a juggernaut.

And then the personal computer hit the market like a storm. Born from a garage and the brains of a couple misfits who saw the future, Apple Computer bundled everything a regular person needed to be productive with a computer: a sleek machine, and an approachable programming language (BASIC) – just plug in a TV and go. IBM shrugged it off as a toy — until it wasn’t. The personal computer became a real threat to the old order of corporate machines.

The rest is history that we all know: the graphical user interface, the internet, the smartphone, the cloud, software as a service, real-time collaboration, and now, the AI assistant. It all seems like the steady march of forward progress...

But what if we've also moved backward?

We lost the plot.

In the beginning, the personal computer was a bold departure from shared mainframes in large corporations. Your computer, your files, and your applications were tangibly yours.

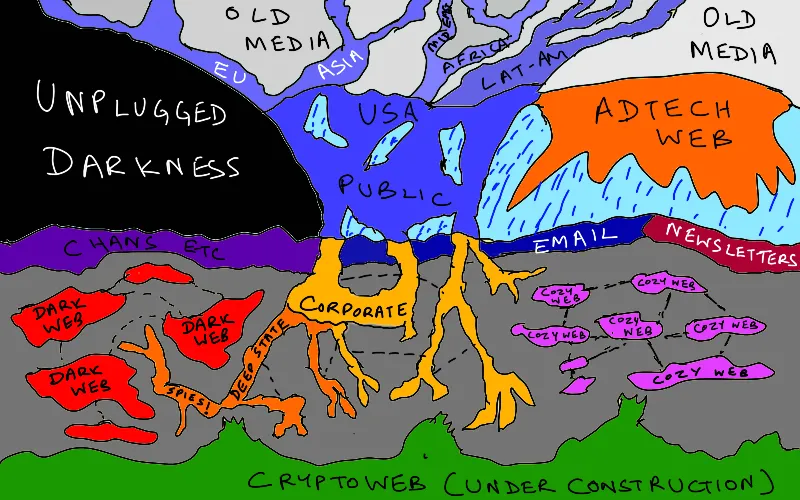

Today, the experience of most computer users is to... just use the internet. And for most people, that means using a handful of cloud services operated by large corporations, who store your data on their own servers, in opaque, inaccessible formats.

The idealism of the '90s web is gone...The public and semi-public spaces we created to develop our identities, cultivate communities, and gain in knowledge were overtaken by forces using them to gain power of various kinds. – Yancey Strickler (2019)

We're so back.

In the beginning, the personal computer was a powerful, infinitely flexible tool for exploring the world of information and ideas. In the words of Steve Jobs, computers were "like bicycles for our minds". In those early days, to programmers and non-programmers alike, the personal computer and the early internet felt like a new horizon unfolding, where the only limit was your imagination.

Access to computers—and anything which might teach you something about the way the world works—should be unlimited and total. – Steven Levy (1984)

The present is a strange, exciting moment in the history of computing. In recent years, LLMs have shown us that soon, anyone will be able to instruct a computer to do practically anything, in plain English. And we're all coming to terms with the cloud. We live in an era where our computers are more abstract, and less tangible. Portable in the physical realm, but locked up in the digital realm.

We believe all of this is a sign that it's time for the computer to change, again.

Our vision for the future

Our vision for the future of personal computing is an intelligent personal server.

- The new soul of your computer is your files, on your server. You should be able to access this new computer-soul from anywhere, upgrade your hardware on-demand, time travel to a past version of your data at any time, and connect to other machines you own.

- Your files, tools, and creations should be less fragmented, and more tangibly yours. On Zo, all files are stored using open file formats. Whenever possible, services are hosted on your server. This includes the Zo application itself, as well as all software created or installed by you or Zo. Your entire Zo Computer can be packaged up, saved, and restored on any machine.

- You should have more custody over your AI. On Zo, you can use any AI model from any provider. All AI memories, search indexes, and settings are stored on your server using open-weight embedding models and open-source software. Our long-term vision is to enable anyone to run, train, and build their own AI models and tools on their own server.

References

- Steven Levy (1984), Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution

- Bill Atkinson (1987), An introduction to Apple's Hypercard

- Martyn Burke (1999), Pirates of Silicon Valley

- Brett Victor (2013), References for "The Future of Programming"

- Yancey Strickler (2019), The dark forest theory of the internet

- Venkatesh Rao (2019), The Extended Internet Universe

- Maggie Appleton (2020), The Dark Forest and the Cozy Web

- Maggie Appleton (2021), Tools for Thought as Cultural Practices, not Computational Objects

- Charmbracelet, Inc (2025), A Brief History of Terminal Emulators